1892–1973

-

Geophysical Laboratory, staff member (1925-1947)

-

B.A. and B.S., University of the South, 1914

-

University of Pennsylvania, 1914-1916

-

Ph.D. in Chemistry, Johns Hopkins, 1920

-

D.Sc., University of the South, 1947

-

National Academy of Sciences

-

Ramsey Fellowship Board

-

Order of the British Empire

-

Geological Society of America, fellow

-

American Geographical Society, fellow

-

Washington Academy of Sciences

-

Royal Institution of Great Britain

|

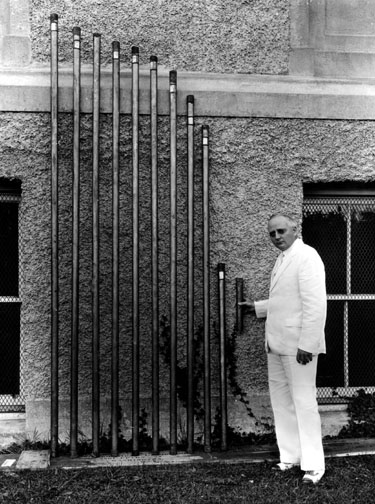

Charles S. Piggot, the founding father of ocean floor marine research served as a Geophysical Laboratory staff member for twenty two years of his professional life. He came to the Geophysical Laboratory in 1925 to conduct research on the importance of radioactivity in geophysical phenomena. To do so, Piggot first studied the radium content of different layers of the earth’s crust. This initial research helped to begin the science of geochronology and revealed the mysteries of radioactive decay systems. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

To improve the quality of his sediment samples, Piggot had to develop adequate coring equipment, as there were no other ocean drilling projects in motion at that time. Up until Piggot's work, coring technology was limited to a grappling device that could only collect small surface samples and often destroyed the stratigraphic record within the rock. The marred samples derived from this method were only capable of providing present ocean basin condition information. For his project, Piggot needed to tap into the past. He had his device in 1936. The apparatus used a powder charge to drive a steel tube into sediment. The charge could be adjusted according to water depth and sediment type. Once sediment was retrieved, the tube split into halves to expose the stratigraphy. The mechanism was capable of obtaining undisturbed cores up to three meters in length. Piggot collected his first core samples while on a cable repair ship traveling from Newfoundland to Ireland. Over the next couple years, he conducted subsequent expeditions to collect more samples from other sites. By the end of his study, Piggot had assembled a large number of sediment dates and sedimentation rates from the North Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Basin that spanned back over 300,000 years. The voyage and ground-breaking information that came from it stirred renewed interest in oceanography and marine sedimentology. Piggot’s research was significant because his sediment layers from the ocean bottom could essentially provide a historical record of the ocean basins, which would therefore offer a detailed account of land processes as well. By unlocking the secrets of the ocean floor, Piggot could understand more about how the earth functions on land. The results from Piggot’s research answered his original question – Is radium simply a surface characteristic? The answer was yes. The high concentrations of radium in ocean sediments did not continue far below the surface. Piggot found exactly what he was looking for and more. Piggot's interests changed during the World War II era to public service related matters. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, he took a leave of absence from the Laboratory to develop procedures for the recovery and disassembly of magnetic and other mines. During this time, he worked on the recovery of submarine mines and the disarming of bombs, booby traps, and other live ammunition. He founded training schools for mine disposal and procedures for stripping dangerous objects. Piggot was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his numerous war-time contributions. After World War II, Piggot moved to London for two years to serve as the first foreign service reserve officer assigned by the State Department. His role was to promote cooperation between the scientists and governments of the United States and Great Britain. Piggot returned to the United States in 1952. He became a consultant and assistant supervisor on a navy project at Yale University. In 1955, Piggot surveyed and appraised eighteen scientific institutions in India for the National Academy of Sciences. Piggot retired shortly thereafter. He was a true pioneer in the scientific community; his work and commitment changed and expanded the world of marine geology and oceanography. Piggot was many things in his lifetime, but he was firstly and foremost a scientist. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

References:

Further Reading:

|