Shaking Things Up

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Carnegie was not the first institution to look into the problem, but it was the first to effectively do something about it. The University of California at Berkeley and Stanford University had published critical warnings in various scientific journals regarding the need for a great American seismology program. The Seismological Society of America had even been around for ten years, but rather than conducting research, it simply encouraged it. The real pioneer and source of stimulation was H. O. Wood. In the late 1910s, he organized and printed a plan for an extensive investigation of West Coast earthquakes. The plan included the number and locations of the necessary stations for a thorough survey of California, along with the essential equipment to do the job. Numerous agencies rejected Wood’s idea before he arrived at Washington to speak with Merriam. Carnegie's president was intrigued by the concept. American seismology was finally on its way. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

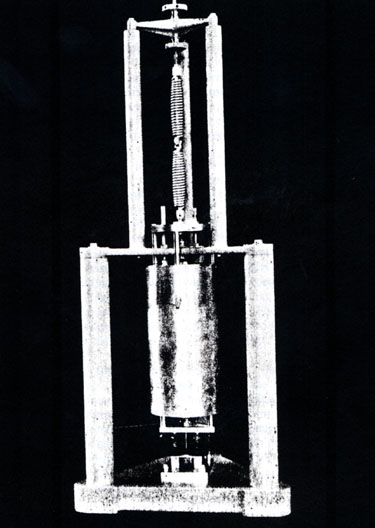

1925 brought the Santa Barbara earthquake, the first earthquake in California within the region observed by the committee. The quake did not derive from the highly active San Andreas Fault, but was a local disturbance from small faults in the Santa Ynez Mountains. The destruction was limited mostly to Main Street and the surrounding areas. Despite its small magnitude, the earthquake succeeded in increasing seismological interest and providing direct information via nearby observation stations. Santa Barbara showed that earthquakes are not confined to the great known faults. The next great earthquake occurred at Long Beach, California on March 10, 1933. The death toll and destruction were significant. Aftershock studies were conducted on tall buildings from the basement up. Of all the earthquakes studied by the committee, Long Beach yielded the most results because it was an area prepared with many observation stations, landmarks, and high precision equipment. It was thus the most detailed study performed by the committee. After fifteen years of involvement in 1936, the Advisory Committee in Seismology gave control of the research program to the California Institute of Technology. The change in power was only natural, as CIT was close to the source and had become increasingly involved in the program since the beginning. A Washington base for a California study was no longer needed. Over the fifteen years, the Advisory Committee in Seismology studied different earth movement components, and from that, produced a number of valuable instruments. Additional studies involved investigations into crustal creep, deep focus earthquakes, and vertical earth movements. Resulting equipment and data included the Wood-Anderson seismograph, new fault zone maps, detailed reports on the San Andreas Fault, recordings on the height of Mount Whitney, the Benioff vertical and horizontal component seismometers, and portable seismometer stations. The Advisory Committee in Seismology enjoyed fifteen long years of excellence in seismology. It established the standard for what today has not only become a hot science, but a means of protection to those living in dangerous areas. Without the events of 1921, it’s hard to imagine what American seismology would be like in the 2000s. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

References:

Further Reading:

|