1869–1960

-

Geophysical Laboratory, director (1907-1936)

-

A.B., Yale University, 1892

-

Ph.D., Yale University, 1894

-

Sc.D., Groningen University, 1914

-

Sc.D., Columbia University, 1915

-

Sc.D., Princeton University, 1918

-

Sc.D., University of Pennsylvania, 1938

-

National Academy of Sciences, secretary and vice president

-

Geological Society of America, fellow, vice president, president

-

Philosophical Society of Washington, president

-

Washington Academy of Sciences, president

-

Franklin Institute

-

Turin Academy

-

John Scott Medal

-

Wollaston Medal (Geological Society of London)

-

Penrose Medal (Geological Society of America)

-

Bakhuis Roozeboom Medal (Royal Academy of Amsterdam)

-

William Bowie Medal (American Geophysical Union)

|

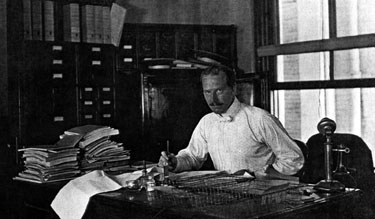

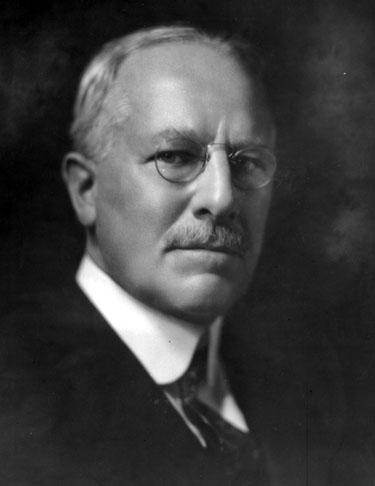

Throughout Arthur L. Day's lifetime, and especially during his years at the Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Geophysical Laboratory, Day’s extensive scientific research spanned the fields of physics, physical chemistry, seismology, volcanology, and glass and ceramic research. Day’s greatest contribution to science is arguably his leadership position as director of the Geophysical Laboratory. When it came time for the Board of Trustees to choose the new laboratory’s first director, Day’s broad experience and sensible nature singled him as the most logical choice. He would hold this position from 1907 until 1936. Prior to his new appointment, Day was an active and enthusiastic employee of the United States Geological Survey. His work in the Physical Laboratory there greatly helped to prepare him for his new role as director. He was also one of the first individuals to receive financial support through grants from the Carnegie Institution of Washington for his scientific research. The first studies at the Geophysical Laboratory concentrated on phase-equilibria of the oxides and sulfides of earth’s crust. In continuation of his previous research, Day extended the standard gas thermometer scale from 1,200 degrees Celsius to 1,600 degrees Celsius in a series of experiments in 1911. This work created a practical temperature scale defined in terms of closely spaced melting points of pure substances. With the temperature scale complete, Day next turned his attention to the geophysics and geochemistry of volcanoes in order to test theories on high-temperature geological phenomena. Day was predominantly interested in the possible water content of volcanic emanations. To test his theories, Day and E. S. Shepherd traveled to the active volcanic region of Hawaii’s Kilauea in 1912 to collect gas samples directly from the liquid lava. Day’s research indisputably answered his initial question-- water vapor was the most abundant component of volcanic gas. From volcanoes, Day shifted his attention to the California geyser basins of Lassen Peak and Geyserville and Wyoming's Yellowstone National Park. Under his direction in 1929 and 1930, the Geophysical Laboratory was allowed to drill boreholes up to 123.8 feet deep at Yellowstone that were merely yards away from the legendary Old Faithful geyser. He later wrote Hot Springs of the Yellowstone National Park with E. T. Allen to report the study's findings. For more information about the Yellowstone drilling project, please see Drilling Yellowstone. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

In 1918, Day took a leave of absence from the Geophysical Laboratory to become the Vice President in Charge of Manufacturing at the Corning Glass Works in New York. He remained there until 1920 when he returned to Washington to resume his director position. Although no longer officially at Corning, Day continued to consult for the company until his retirement in 1936. Upon returning to the Geophysical Laboratory, Day helped take the institution in a completely new direction. From 1921 to 1936, he served as the Chairman of Carnegie’s Advisory Committee in Seismology. The idea for a seismological committee originated from H. O. Wood’s 1916 paper, in which he presented a detailed plan for collaborative seismological research in California. The only component Wood’s plan lacked was a financial backer, and that’s precisely where the Carnegie Institution of Washington stepped in. The committee began its research in Southern California and focused on five major studies: geology along the fault zones, surface displacement, continuous seismological observation stations, observation equipment, and gravity determinations. These five areas of research set a clear foundation for study and growth over time. With Day’s retirement in 1936, the Geophysical Laboratory passed control of the seismological laboratory in Pasadena to the California Institute of Technology. Day is credited with a great deal of the committee’s success. Philip Abelson, director of the Geophysical Laboratory from 1953 to 1971, stated that in reference to Day’s work for the Advisory Committee in Seismology, that “Dr. Day can properly be given credit for stimulating seismology in the United States and raising it to a level of sophistication that it had not previously known.” For more information about the Laboratory's seismological investigations, please see Shaking Things Up. In 1925, the Geophysical Laboratory turned its attention to yet another field-- radioactive research. Under Day’s direction, Charles Piggot developed a coring gun that was able to obtain sediment samples from the ocean bottom to test for radioactivity. Day’s last areas of interest remained in seismology and hot springs. After his retirement, Day traveled to the volcanic areas of New Zealand to conduct studies on the region’s activity. However, he was forced to give up his research after an unfortunate physical breakdown in 1946. The end eventually came in 1960. Day is remembered for his personal research, unwavering leadership, and his endorsement of often overlooked scientific programs. The Arthur L. Day Medal was established in his honor by the Geological Society of America. Day was a true pioneer, both in and out of the laboratory. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

References:

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Further Reading:

Links:

|